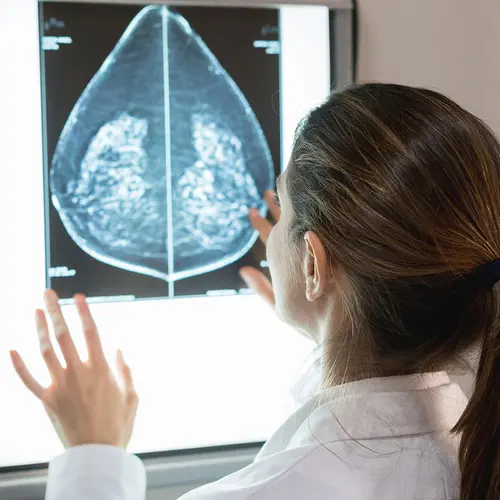

March 4, 2025 – What if women diagnosed with low-risk breast cancer didn’t get the standard lumpectomy, but instead closely monitored their health with twice-a-year mammograms?

A recent study showed that the two approaches led to similar rates of eventually developing invasive cancer after two years – 4.2% for those who chose “active surveillance” and 5.9% for standard treatment, typically surgery and radiation.

Both groups had similar rates of worry, anxiety, and depression during those two years.

More than 62,000 women in the United States are diagnosed yearly, via mammogram, with a noninvasive cancer of the cells lining the milk ducts. It’s called “ductal carcinoma in situ,” or DCIS, considered “stage zero,” or the earliest form of breast cancer.

Typically, this is treated by surgery (a lumpectomy) followed by radiation. That’s because doctors can’t tell if DCIS will become invasive.

The current monitoring trial is reminiscent of the “watchful waiting” approach to prostate cancer in men, involving regular exams before patients opt for surgery if the cancer spreads.

The trial is exploring options of treatment and weighing the risks – meaning both the risk of cancer spreading or returning, and risk of a lower quality of life. That balance varies for each person.

Surgery or Surveillance?

Women in the active surveillance group get mammograms twice a year. If anything concerning turns up, biopsies are taken to help find out the standard treatments should be started. The approach caused some controversy.

“There were a lot of people who were accusing us of putting patients in danger and saying they’ll all get cancer, so it was really important for us to show in the early part of the study that it was safe,” said lead researcher Shelley Hwang, MD, MPH, director of the breast oncology program at Duke Cancer Institute in North Carolina.

Criticism renewed when the two-year results were published in December. Monica Morrow, MD, chief of breast surgery at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, said that based on past research, it’s highly likely that some women in the surveillance group have invasive cancer in their bodies right now.

“The only question is, how big is that risk?” said Morrow, who co-authored an editorial in TheJournal of the American Medical Association alongside the main report on the two-year results. “If you have a small area of DCIS, you can go to the operating room and have a lumpectomy, which takes an hour. It leaves you with a scar on your breast.

“For small DCIS, if it’s done by someone who knows what they’re doing, it doesn’t change the size or shape of your breast, and you know for sure that you do or don’t have invasive cancer, so it can be treated properly. You know exactly how much DCIS you have, so you can calibrate your risk for deciding whether or not to get radiation. And you can take tamoxifen or not take tamoxifen.” Tamoxifen is a hormone blocker that prevents estrogen from attaching to cancer cells, stopping their growth.

Of the surveillance group, Morrow said: “You’re going to get breast X-rays twice a year, with the anxiety that’s associated with waiting to find out if there’s something bad there.”

In general, the risk of going on to die from breast cancer within 10 years of a DCIS diagnosis is around 2% among those who get standard treatment. One study in the Netherlands found that women diagnosed with DCIS and treated have a normal life expectancy.

The trial is called COMET, for Comparing an Operation to Monitoring, with or without Endocrine Therapy.

Hwang said the purpose of the trial is to “give some information to patients about what would happen if you did something different from the standard recommendation. Because if we continue to do what we’re doing because it works, we would never make any progress. The fact that patients do so well indicates that there might have been some patients who did perfectly fine even if we did nothing to them.”

Hwang added: “If all women went out and got a double mastectomy, then they would also end up having a 1% likelihood of having [breast] cancer.”

The Struggle of Making a Decision

The women in the COMET trial will be followed for a total of seven years. The second part of the study will look at differences between the active surveillance group and the treatment group regarding mental health, quality of life, physical pain, body image, and a measure called “decisional regret.”

At the two-year mark, most of those measures didn’t have notable differences between the two groups and were actually lower than previous research studies had found among women with DCIS. One possible reason: People who joined the study knew they may be randomly assigned to either group, said Ann Partridge, MD, MPH, interim chair of the Department of Medical Oncology and Adult Survivorship Program director at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Massachusetts.

But there were some people in both the surveillance and the treatment groups who struggled with worry or who got depression by the two-year mark. In statistics, those are called outliers.

Partridge said an upcoming analysis will look at outliers to find out “what are the predictors of having a really hard time with more aggressive therapy for DCIS. That may be an area where we say, ‘OK, this person may really benefit from a certain approach, ultimately, because they’re at higher risk of having a hard time, even if it’s not going to change how they do in the long run.’ ”

Partridge said the five-year results should help show whether active surveillance is best for some women, since two years isn’t long enough to find out the ongoing cancer risk.

It’s clear that women in the COMET trial varied in their desired approach to addressing their DCIS diagnoses. After they were randomly assigned to either surveillance or traditional surgery and radiation, many flipped to the treatment they weren’t assigned to. In the group where surgery was recommended, just 52% of the women had gotten surgery within six months of the trial’s start.

Women with breast cancer often report long-lasting regret about their decisions and what scientists call decisional conflict – not being certain about which option to choose.

“When we’re experiencing a high level of stress, we tend to make worse decisions,” said Alannah Shelby Rivers, PhD, a social psychologist who studies treatment decisions. “And that is very much true in breast cancer treatment decision-making, specifically. There have been several studies showing that when you’re having more of these negative, intense emotions, people make decisions that in retrospect they regard as less satisfying.”

How to Reduce the Stress of Choosing Treatment

Researchers say social support and clear answers from doctors can help reduce the chance that you'll dislike treatment decisions.

“It’s very difficult to think about how to encourage these better decisions because sometimes, having more information isn’t necessarily the answer,” Rivers said. “Social support can be very beneficial, both from family and friends, and then the support and alliance you have with your medical practitioner.”

Feeling like your questions have been answered by your doctor is also important, said Rivers, who is an assistant professor at Texas Woman’s University.

Her own research found that as many as 1 in 5 women with breast cancer have severe distress.

“That’s probably outside of what social support, doctor’s assistance, and information can address. I think that you need, in that case, psychological resources to help with that in addition to decisional supports,” Rivers said.

One person in the COMET trial, Bonny Moellenbrock, says clear answers were crucial to her decision-making. The 54-year-old social enterprise and investing consultant from Durham, North Carolina, joined the trial after getting a second opinion on her DCIS diagnosis from Hwang at Duke Cancer Institute. Her husband, a hospice nurse, went with her on visits, and the three discussed a range of topics, including radiation treatment and its side effects. There was a lot of information to digest, she said.

“If I had been assigned to the standard-of-care group, I probably would have gone ahead and done it because that’s how it works,” she said. “I feel like I was lucky that I ended up in the monitoring group because that’s really what I wanted, but there was no other way to do that where I could be monitored regularly and feel like I was being responsible for my health. You needed somebody to tell you it was OK to take this path.”

During the trial, mammograms revealed spots that required several biopsies. She has read about how medical technology is getting better at finding DCIS.

“And we’ve realized, wow, this isn’t killing everybody, so is there a better way?” she said. “Participating in this study helps advance what we know, and that’s really important so we can do better.”

Moellenbrock is among the more than 70% of women in the surveillance group who decided to take a hormone-blocking treatment aimed at stopping cancer growth. Hwang said one of the next analyses researchers will do is to see what, if any, protection the therapy may have during active surveillance.

“We do know that the cancers that developed in the group of patients who are on active monitoring were no different in terms of the size and whether they were hormone-positive and whether they needed chemotherapy,” Hwang said. “So there was no difference between the cancers that were identified in one group versus another. We just found fewer of them in women who are on active monitoring, and that was probably because a large number of those patients had some sort of endocrine therapy.”

And if hormone-blocking therapy doesn’t appear to make a difference, that’s important information to share during decision-making, too, Hwang said.

“We don’t understand whether endocrine therapy had an effect on the lower risk of cancer in the patients who are on monitoring, but it would make sense because we use endocrine therapy for women who we think are at increased risk for breast cancer, and we know that that reduces their chance of having cancer,” she said. “It’s very possible that it helped these women as well, but whether it needs to be part of active monitoring, I think that’s for future studies to determine.”